Ask An Arborist: April 1, 2010

|

|

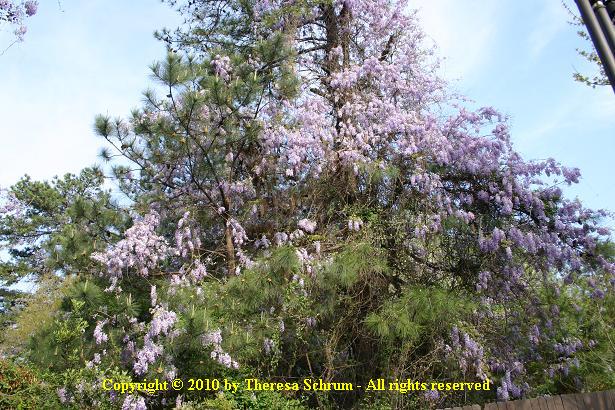

| Asian Wisteria |

English Ivy |

William in Griffin Writes:

"I have several trees in my yard that the previous owners planted English ivy underneath. The ivy has climbed up the trunks of the

trees and into the branches. It looks nice but I'm concerned it may be hurting the trees. Should we remove the ivy?"

The short answer to this question is yes. English ivy can be a tree killer. However, not all vines are going to do harm to trees.

I posed this question to Art Morris, Board Certified Master Arborist with Bartlett Tree Experts. His response was:

"English ivy, kudzu and other climbing vines are more than just an

eyesore in trees; they can cause both structural and health problems if

they're allowed to climb tree trunks. When ivy is allowed to grow around

the base of a tree if forms a dense mat covering the tree's buttress

root flare. The dense ivy bed often causes leaves and debris to pile up

against the root collar, and traps moisture against the trunk and root

flare. This can lead to several diseases as well as potential structural

decay at the base of the tree. Additionally, when ivy vines grow up a

tree trunk and reach the canopy the vines contribute significantly to

the wind or ice load potential, which can lead to breaking limbs or

falling trees. After all, trees are well adapted to stand up by

themselves, but they're not very good at holding up hundreds or

thousands of additional pounds of ivy."

Not all vines can cause harm or kill trees. Depending upon the vine, some can be allowed to climb trees others have to be

managed and still others should be kept away from trees at all costs.

Native Versus Non-Native and Other Factors...

Believe it or not, the fact that a vine is native or not may not be the defining criterion for vines that can harm trees. We have

some fairly aggressive native vines that I wouldn't turn loose in my trees, yet there are some non-native vines that with proper

management won't be too much of a problem and vice versa, of course.

The factors that I believe determine if a vine can do detriment to a tree are its rate of growth, mature size,

how it attaches to the tree, it's native environment and whether it's evergreen or not. Being biased towards native plants, I'm

inclined to be a bit more forgiving to native vines growing in their natural environment.

Fast-growing vines and ones that are going to grow to an enormous size should raise red flags when it comes to trees.

In addition to Art's answer above,

these vines can quickly overpower a tree and leave it susceptible to competition for light and resources as well as add an enormous

amount of additional weight to the tree making it susceptible to falling in wind and ice. If the vine in question is also

evergreen, then you have a real potential tree killer. Four common

landscape vines having these characteristics are: English ivy, Confederate jasmine, Japanese honeysuckle and Carolina jessamine.

Three of these vines are non-native and the Carolina jessamine is native. English ivy and Confederate jasmine attach to trees using

aerial roots. Japanese honeysuckle and Carolina jessamine will twine around the tree as they grow. Because English ivy is so

shade tolerant, it can progress across the forest floor from one tree to the next. All of these vines should not be allowed

in trees, whatsoever. Note: English ivy and Japanese honeysuckle are listed as non-native invasives in the South. These vines are

so destructive that they should be eliminated from the landscape.

Another usually non-cultivated but native vine called catbriar (Smilax spp.) can also be a problem. It's commonly found in

woodland areas with heart-shaped evergreen/semi-evergreen leaves, green stems and wicked thorns. I try to keep this vine confined

as much as possible.

Vines that are fast-growing, large yet deciduous (lose their leaves in winter) or even annual aren't necessarily any better than

their evergreen counterparts. They, too have the capability of shading out the tree's leaves, adding weight and even girdling

(strangling) the

tree's limbs and trunk. Some common vines in this category are: Chinese/Japanese wisteria, kudzu, muscadine, trumpetvine and

pipevine. Annual vines include hyacinth bean and numerous varieties of morning glory.

Muscadine, trumpetvine and pipevine are all native and usually confine their growth to trees at the edge of woods or those that

are standing alone. Therefore, they don't represent a threat to the forest overall, but they can take their toll on individual

trees.

On the other hand, non-native wisteria and kudzu can take over large stands of trees rather quickly leading to tree death. Wisteria,

kudzu, muscadine and pipevine grow by twining. Trumpetvine has aerial roots but also tends to twine as it matures. Annual hyacinth

bean vine produces a thick growth of large leaves that can shade any tree that it's growing into as will morning glories which have

the added problem of producing hundreds of seeds and becoming invasive. Note: Asian wisteria and kudzu are also considered so invasive

and damaging that removal is highly recommended.

|

|

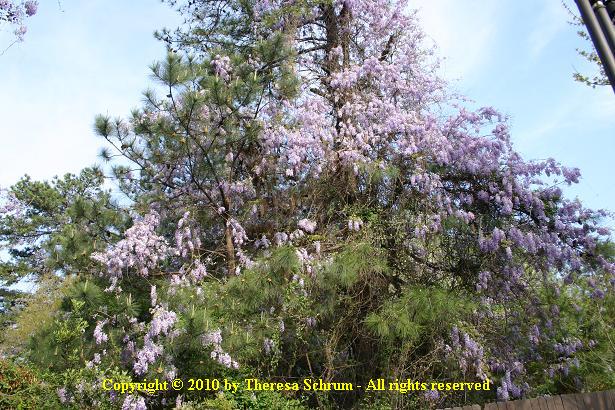

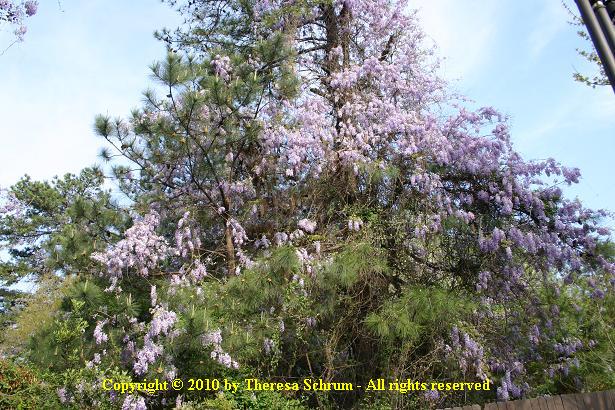

| Wisteria Supporting a Dead Pine |

Kudzu |

Vines that are smaller and grow more slowly can usually be allowed to grow on trees. There are both

native and non-native vines that I would put into this category: cultivars/hybrids of clematis, crossvine, Virginia creeper,

virgin's bower (native clematis), Carolina moonseed, maypop (native passion vine) and poison ivy. With the exception of the

clematis cultivars, all of these

vines are native. Although Virginia creeper and crossvine can grow quickly and

get large, I cannot remember ever seeing any tree so overgrown with them as to pose a problem even though crossvine can be

evergreen. The clematis vines (including the native), Carolina moonseed and maypop climb by twining. Crossvine, Virginia creeper

and poison ivy climb by using their aerial roots.

|

|

| Virginia Creeper |

Poison Ivy |

People often confuse Virginia creeper and poison ivy. Just remember this little ditty:

"Leaves of three, leave it be. Leaves of five, leave it alive."

And before anyone jumps down my throat about the poison ivy, I would like to remind everyone that the Audubon Society considers

poison ivy to be one of the top foods for song birds, with about 60 species feeding on the berries. It's so important, they have it on

a poster of important plant foods for birds. However, I digress.

Should you decide to let a smaller, slower-growing vine grow up a living tree, be prepared to manage the vine by cutting it back

to keep it confined to the trunk and not allow it to grow on the limbs which could add weight and change the tree's center of

gravity as well as shade the tree's leaves. Make sure that fallen leaves and other plant debris don't collect at the bottom of the

vine against the host tree or as Art says, diseases may follow. Should a tree that is hosting a vine show signs of stress,

the vine will have to go for the health of the tree.

One last thought. Dead trees that are left standing (snags) can be used for vines. Just remember that this arrangement will be

temporary as the snag will eventually decay to the point of falling. Just make sure it won't hit anything when it comes down.

Please email me if you have any questions or topics you would like to submit

for later articles.

If you are concerned about the trees in your landscape, you can contact a Certified Arborist or a professional tree company in

your area through the web site of the

Georgia Arborist Association.

Unless otherwise noted, Images & Drawings Copyrighted © 2010 by Theresa Schrum - All rights reserved